My parents, John Whitelaw and Alvis Love, came of age during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The Depression affected many countries, and was a spur to the development of both Communism and Fascism in Europe, as capitalist financial systems were seen to have failed. The U.S. was hit particularly hard. The stock market crashed in 1929. By the early 1930s, a quarter of all wage-earning Americans were unemployed. There was no national unemployment insurance or welfare, so when Americans stopped earning, they also stopped spending, thus accelerating the downward spiral of the economy. These events caused massive personal suffering; further, many people worried that our economic and governmental systems had permanently failed, and the American dream was over.

John, in the Midwest, and Alvis, in Oregon, both graduated from college in the depths of the Depression; their personal journeys into adulthood interacted deeply with the circumstances of this historic era. Their adult lives were forged in the maelstrom of the Depression, and as social workers in this era, they were able to make a real contribution to their country.

John’s Kansas Years

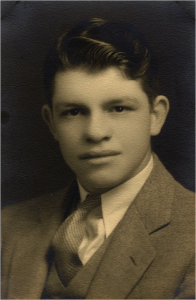

John was born in 1911 on a family farm near Lawrence, Kansas. The Whitelaws did not prosper in farming, and lived with scanty material resources. John and his two older siblings, Neill and Eleanor, completed the elementary grades in rural, one-room schoolhouses. Later, they walked or drove a horse and buggy the two miles to high school.

Franklin School, near Lawrence, Kansas, 1916. John is seated at lower left. Eleanor and Neill are in the second row, second and third from left.

In the midst of material poverty, however, the Whitelaw children were fortunate to grow up in a household that held education in high esteem. Their mother, Bertha, unusually for the time, had graduated from college with a major in Greek and Latin, and was valedictorian of her class. Their father, John, had also received some college education. All three of the children graduated as high school class valedictorians. John followed his brother and sister to Park College, Missouri, founded to provide academically promising but poor Midwesterners, mainly those from a farm background, with a college education. Tuition was free, as the students worked half of each day on the college’s farm and cottage industries. John spent two years there, and then transferred to the University of Wisconsin where he majored in economics and business administration.

John graduated from college in 1932, in the middle of the Great Depression. He hoped to find a job in Chicago but his job search was disappointing. He wrote to his cousin, Mary:

“Well, here I am still in Chicago and still very much unemployed. . . . I almost had a job selling Electrolux [Vacuum] Cleaners but you see I am single, young, not a resident of Chicago, etc., and all of that greatly detracted from my hirability in the eyes of the manager. Jobs are really scarce here though and salaries are very low as evidenced by the fact that one of the agencies where I thought about applying told me that I would be lucky to get $15 a week as that was all many firms were paying to experienced men.”[i]

He finally had to return home to Kansas. Going back to the farm was discouraging for him and probably wasn’t easy on his parents, either. John recounted that his father “informed him that things on the farm were not better because of the help of a son with a degree in economics.”[ii] After almost two years of unsuccessful job hunting, his break finally came. In 1934, when he was 23 years old, John became a caseworker at the welfare relief office in nearby Johnson County, Kansas.

After Wall Street had crashed in 1929, Kansas, an agricultural state, felt the effects primarily in the decline in prices for farm products. According to a historian of the era, the value to farmers of wheat sales fell catastrophically from $153.5 million in 1928 to a paltry $29 million in 1932, and the number of employed people declined 30 percent during the same period.[iii]

President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal unfurled an array of programs to help states provide relief to their citizens. For the first time, the federal government became involved in providing economic support directly to the destitute. Previously, a patchwork of local governments and private charities had offered limited relief on a case-by-case basis.

In 1933, Kansas had almost 50,000 families on relief. The welfare agency John joined was a county relief program that had recently received an influx of federal funds. John’s job was to do “Rural Rehabilitation”, which, in addition to providing cash grants to eligible families, also helped them start subsistence farming so they could at least feed themselves, even if selling crops was no longer possible.

One of the goals of the newly founded federal welfare programs was to increase the professional abilities of the staff. John, after nine months on the job, received one of the welfare department’s scholarships to attend graduate school in St. Louis for one semester.

After this additional education, John, now aged 24, was appointed “Poor Commissioner,” as the County Administrator was then called, of the Lane County Welfare Office, located in arid western Kansas. This area was part of the “dust bowl,” and became notorious as an emblem of the wretched condition of many Americans during the Great Depression. About 80,000 people left Kansas during the 1930s, many of them young men who “faced with drought, dust storms, and grasshoppers – had become disillusioned with life on the farm.”[iv] In many cases the emigrants left their aging parents to survive as best they could on the desolate, arid farms.

As the County Administrator, John oversaw the work of the casework staff, which allocated grants to needy families and arranged for basic health care. He also managed the budget, and was the public voice of the program, interpreting this new idea of a federally funded, professionally staffed program to help the indigent and unemployed. His salary was $125 a month.

Christmas card that reads: “To John Whitelaw from Helen Martin. Here’s thanks for getting my tonsils fixed.” One of John’s tasks was to help people get basic medical care, using a combination of private charity and public money.

The profession of social work was relatively new when John came of age. The professionalization of a field that had been filled previously by well-meaning volunteers and religious organizations was given impetus by the events of the New Deal, which required a professional work force to administer its programs. John was well-suited to the demands of this emerging profession. He felt genuine concern for others, was affable and well-liked, and he believed in the values and ideals expressed by the New Deal, that effective government could improve the lives of its citizens and stabilize the democratic system. He also was an engaging public speaker, and could accomplish very well one of the key roles of welfare administrators, that of interpreting the program to clients and the community. He communicated a fundamental decency and kindness that defused the anger and frustration that were so much a part of the welfare office atmosphere at this time. At the same time, he could reassure those who worried about fostering dependency that the program, in addition to offering cash relief, also expected clients to help themselves.

John remained at the Lane County Welfare office for about a year and then continued his social work education in graduate school, this time at the University of Chicago’s School of Social Service Administration. The School specialized in educating administrators for the newly developing federal and state welfare bureaucracies, and many social work leaders were on the faculty. John financed his education through federally funded graduate assistantships. His master’s thesis was on philanthropic foundations, and their role in community planning and development of social programs. He graduated in August 1937, when he was 26 years old.

Oregon

Upon graduation, John was hired by the Oregon State Relief Commission, as the public welfare agency was known at the time, as a caseworker in Clatsop County (Astoria), where the Columbia River meets the Pacific Ocean. Norris Class, a welfare administrator, brought to Oregon a number of young men who were recent graduates from schools of social work around the country. From this cadre came leadership for social work in the Pacific Northwest that lasted for decades.

The job Norris Class was offering John was to establish a child welfare department in Clatsop County. Child welfare workers had master’s degrees, and were expected to offer consultations to the rest of the public welfare staff on difficult cases. They worked closely with other community services for children and were the public voice of the agency, interpreting the new welfare programs to the community. Norris offered John a starting salary of $175 a month plus mileage at 4 cents a mile. John was expected to provide his own car.

“Building Human Happiness”

In September, 1937, when John arrived in Oregon, another arrival to the State was making news. President Franklin Roosevelt came to dedicate one of the glories of the New Deal – Timberline Lodge on Mount Hood.

It is hard to overestimate the impact of the New Deal in Oregon or the popularity of its programs among the citizens. The Great Depression had hit Oregon very hard. The economy collapsed, with the price of wheat and lumber, mainstays of the economy, in steep decline. There were runs on local banks and bank failures; people defaulted on mortgages and were left homeless. “Hoovervilles,” named after President Herbert Hoover, were shanty towns that the newly homeless constructed all over the U.S. Portland, Oregon’s largest city, had at least three.

Although the political leadership of Oregon by and large opposed the New Deal, fearing the incursion of federal authority, ordinary citizens were enthusiastic. New Deal programs, in addition to providing work relief to thousands of unemployed Oregonians, undertook a massive building of infrastructure in the State. In assessing the impact of the New Deal, historian William Robbins highlights the point that ordinary citizens saw the federal government as the source of hope, innovation, change, and effective leadership. He describes the great sense of purpose felt by those involved in New Deal projects, not only to avert a present crisis but to build a better country:

“Although not all of the social experiments were successful and lasting, the social vision and common purpose of New Deal reform was pointed toward building a nation whose benefits and privileges would be extended to everyone. . . . President Roosevelt observed that the great construction projects in the American West would benefit the entire citizenry, with the ‘objective of building human happiness.’”[v]

Alvis Love in Oregon

Alvis was born in Oregon the same year as John, 1911. Her mother had deep roots in Woodburn, an agricultural town near the State capitol of Salem, and Alvis sometimes lived with her grandparents there. Her father, Olin, who grew up on a Michigan farm, was a traveling salesman for an agricultural supply company, with a route covering Oregon, California, and Washington.

Neither parent had attended college, but her father in particular was eager for Alvis to go. She enrolled in Willamette University, in Salem, in 1929. After the death of her father at the end of her freshman year, she had to struggle to continue at college and to provide some financial support to her mother, Mabel. Through part-time work and loans she was able to graduate in 1933. She majored in French, with the thought that she could find work as a French teacher, and with the hope that once she paid off her loans she might be able to attend graduate school at Middlebury College, a training ground for the foreign service. However, the realities of the Depression caused her to put those plans aside.

Upon graduation, she heard that the State was taking applications for the newly established Oregon State Relief Administration. She was hired immediately, along with a large number of other young people, to staff the new organization. The facilities and the work structure were very provisional. The office was in a warehouse, Alvis recounted,

“with a huge corridor down the middle. There weren’t enough offices so we caseworkers had desks of a sort lined up along this big corridor and apple boxes for the clients to sit on while they were being interviewed. The applicants for assistance or for one of the jobs created by the Works Progress Administration would wait in lines stretching clear down the hall. Some were belligerent. They were family men, responsible people, some with college degrees, and here was this young woman deciding if they would get help! Interviewing people who knew me or my family was awkward, such as the math teacher who had been my tutor.” [vi]

“Rough and Ready” Social Work

Two of Alvis’s clients at a transient camp. The photo was enclosed with a card which read, “To Miss Love, From 14 boys who have just lost a little sister.”

Welfare work in these desperate times was sometimes dangerous. The clients were often very frustrated, and some became rebellious. Alvis remembered that once some clients rioted at the office and barricaded in all the workers, until the police came and let them out. On another occasion a man locked her into the house with his family and threatened her with a knife if she didn’t authorize more relief. She refused to concede and he finally let her out unharmed. Another time she visited an ill client who turned out to have small pox. Alvis escaped quarantine but unfortunately exposed her whole office before the illness was discovered and they could all get vaccinated.

At one point, Alvis had a caseload of single men, living in single room hotels on skid row. She said, “It was odd they gave a caseload of single men to a young woman right out of college, but in those days the agency’s priority was to find and help people who were desperate for food.” She had to prowl around the waterfront looking for them. One man wrote her amorous and semi-threatening letters. The authorities deemed him mentally ill and he was committed to a mental hospital. She said she never had any real concerns for her safety: “It must have been a more innocent time.” Two of the men on her caseload looked after her; when she visited the men in their hotels, they let everyone know she was coming and accompanied her on her rounds. When she left that caseload, they gave her a desk set.

Like John, Alvis was able to attend one semester of graduate school at the expense of the welfare department. There was no school of social work in Oregon so she attended the University of Washington in Seattle. She remembered graduate school as

“sort of hilarious, something to do with the temper of the times. We drank sloe gin because it was cheap. We had frequent gatherings and picnics, where we danced the schottische and other square dances. The faculty and Dean danced, too.”

County Administrator

Alvis, as a County Administrator, had to have a car in order to travel over the entire county. Buying one’s own car and driving it as part of the job, at a time when car ownership was not universal, gave these young professionals a sense of independence and personal freedom.

After one semester of graduate school, Alvis was promoted to County Administrator, just as John had been in Kansas. Her first job was in Columbia County (St. Helens), where the County Board of Commissioners, who had traditionally handled relief efforts, was in a power struggle with the State Welfare Office, which thought it was now in charge. The County Board fired every Administrator who was sent to them, including Alvis. Her next position was Administrator of Benton County (Corvallis). Her main memory of that job was that during one severe winter, when the roads became impassable, she carried food up a mountain to a snow-bound family stranded there because they all had the flu.

As Administrator in Linn County (Albany) Alvis, now 26 years old, experienced sexual harassment, an occupational hazard for young professional women of the time. She recounted:

“A prominent doctor on the State Medical Board and also on the State Welfare Commission requested that I confer with him on welfare cases. When I would get to his office, he would lock the door behind me and sit me down right by him and haul out a bottle of whiskey. He tried to get me to drink with him. I would try to get the information I needed and get out of there. Sometimes he chased me around the desk. When I would leave, his office staff looked at me with sympathy. He never did anything to me, but it was a constant effort to fend him off. I would get back to my car and be soaking wet from perspiration. He figured caseworkers were fair game. I knew if I reported it, he could have had me fired because he was on the State Welfare Commission. I wouldn’t have been able to get another job, because there were no jobs. I have a lot of sympathy for women now who are involved in reporting these situations.”

John and Alvis

Welfare staff picnic on Memorial Day 1938 at the Oregon Coast. Here John and Alvis began a serious relationship. Alvis and John are third and second from right. Norris Class, who hired John and many other young social workers from around the country, is on the far right.

John had been stationed in the rural back-water of Clatsop County (Astoria) for only eight months when his life suddenly became much more eventful. In May, 1938, he was brought into the State Office in Salem, Oregon, to clear up an administrative problem involving an incompetent county administrator. He was now at the nerve center of New Deal administration in Oregon. Through a mutual friend, he met Alvis, now 26 years old and the County Administrator of Linn County. They were both part of a large group of young professionals around the State working for welfare who got together to socialize. At a Memorial Day beach party John and Alvis started dating, and on Labor Day of that year, they got married after only a three month courtship.

Both John and Alvis left the welfare program within a year or two of their marriage. By the late 30’s, the nation was beginning to recover economically, the sense of emergency was over, and the welfare offices were becoming institutionalized as governmental bureaucracies.

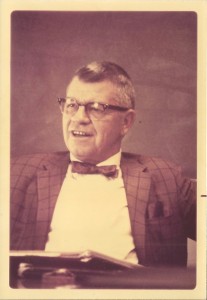

John took a position as head of the Community Council in Portland, a position he held for the next twenty-three years, with a break during World War II when he served in the U.S. Navy on a gunnery ship in the Aleutians.

John Whitelaw at his retirement party on leaving his position as Executive Director of the Portland Community Council, Portland, 1963.

The Community Council gave leadership to social work agencies, and worked with service organizations and local business leadership to improve social services in the metropolitan area. After retiring in 1963, John joined the faculty of the newly founded School of Social Work at Portland State University.

Alvis quit work to raise three children, John (born 1939), Susan (born 1942), and Nancy (born 1947). She returned to her social work career in 1957. She always regretted that she had not been able to continue her graduate education, but with a family to raise and the lack of a school of social work in Oregon until very late in her career, it never seemed feasible to return to school. She became the Associate Director of a large family service agency in Portland. She then worked as a consultant for the State Child Welfare Department, in which she traveled all over the State helping local offices establish child protection programs that enabled children to remain safely in their own homes. She retired in 1981.

Alvis Whitelaw with one of her staff at the time of her retirement from Metropolitan Family Service, 1976, Portland, OR

John and Alvis remembered their years as social workers in the Depression, when they were in their 20’s, as exciting and fulfilling ones. Years later, Alvis reflected on the turbulence of those years.

“It was an exciting time to be involved, to see a big problem like this and the programs really swing into action. At first we were providing relief, and then they set up the Works Progress Administration, and our job was to interview people and refer them for job programs. They built roads and bridges and other things all over the state. There was the Civilian Conservation Corps for young people. It was just exciting to be there. I really have never gotten over the exhilaration of that time. We certainly weren’t doing skillful family counseling. We had a feeling that the whole nation was being moved very fast in some direction, and of course it was, with Roosevelt.

We were all excited about Roosevelt and his plans to keep people from starving to death. We had a sense of purpose. We were all united by the feeling we could make a difference in this horrible situation. Welfare services delivery in those years was a rugged affair – rough and ready. These guys needed jobs, so the federal government hired them and made work of building roads and so on. It all seems so simple, looking back.”

[i] Whitelaw, John. (1932) Letter to Mary Williams. Whitelaw family papers, located with Susan Whitelaw.

[ii] Gale, Hugh. (1968) Concern for others runs deep in Whitelaw family. The Clarke Press, Portland, OR, April 3, page 1.

[iii] Fearon, Peter. (2007) Kansas in the Great Depression. University of Missouri Press, Columbia, MO. P. 12.

[iv] Fearon, p. 150.

[v] Robbins, William G. (2008) Surviving the Great Depression. The New Deal in Oregon. Oregon Historical Quarterly, Summer. P. 10.

[vi] Whitelaw, Alvis (1990-1998) Oral History. Dictated to and transcribed by Susan Whitelaw.

How you are related to John and Alvis (Love) Whitelaw. Look on your personal ancestor fan chart (the one with you at the center.) John and Alvis are in the third or fourth ring out from you, depending on whether they are your grandparents or great grandparents.