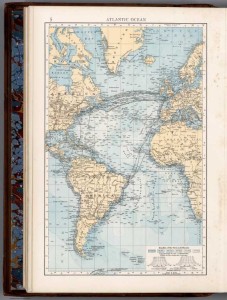

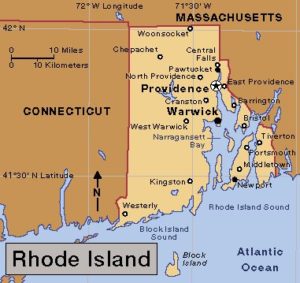

The entrepreneurial spirit and the quest for greener pastures, passed down through the generations of our Love family line, resulted in a two hundred year, seven-generation migration from Northern Ireland, across the Atlantic to the eastern seaboard of the American Colonies, through Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, Ontario, Michigan, Wisconsin, and finally the West Coast states of Oregon and California. The Love family exemplifies a common American migration pattern, with each succeeding generation migrating further west.

The entrepreneurial spirit and the quest for greener pastures, passed down through the generations of our Love family line, resulted in a two hundred year, seven-generation migration from Northern Ireland, across the Atlantic to the eastern seaboard of the American Colonies, through Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, Ontario, Michigan, Wisconsin, and finally the West Coast states of Oregon and California. The Love family exemplifies a common American migration pattern, with each succeeding generation migrating further west.

Our Love family line is male, going from father to son as follows: Adam Love, Sgt. Robert Love, Robert Love Jr., Levi Love, Lorenzo Love, George Winslow Love, and Olin Wayne Love, my grandfather. Olin had one child, my mother, Alvis Ruth Love Whitelaw.

The records we have on these men reveal another pattern passed down through the generations: as a group, the Love men appear to have been personable, capable, risk-taking, and adventurous. They were also dreamers whose big plans didn’t always work out, and the records are punctuated with bankruptcies and broken dreams.

The marriages of the generations of Love men formed a third pattern. As it happens, they tended to marry women whose families had been in North America for a very long time, often back to the earliest European settlers on North American shores. I have written about some of these early families in previous blog posts, and will give links to these earlier posts as each wife appears in the generational narrative. In this way, the reader can make connections among the various early branches of the Love family and form a coherent picture of the extended Love family tree.

As the families moved through history, they interacted with events of their time. This narrative will interweave these economic, political, and social events with the individual life courses of our Love ancestors, from colonial days to the twentieth century.

Historical Background

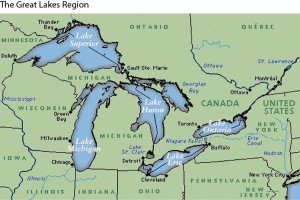

The migration of New Englanders to Western New York and the Great Lakes States after the Revolutionary War.

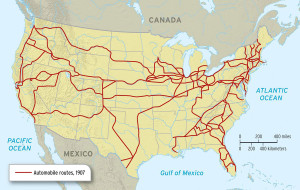

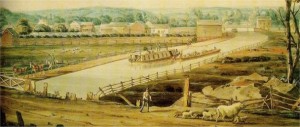

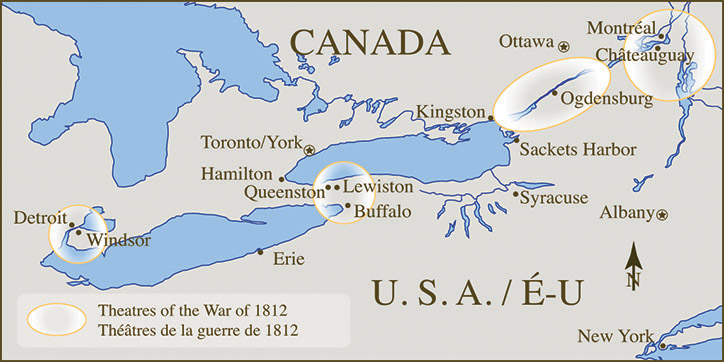

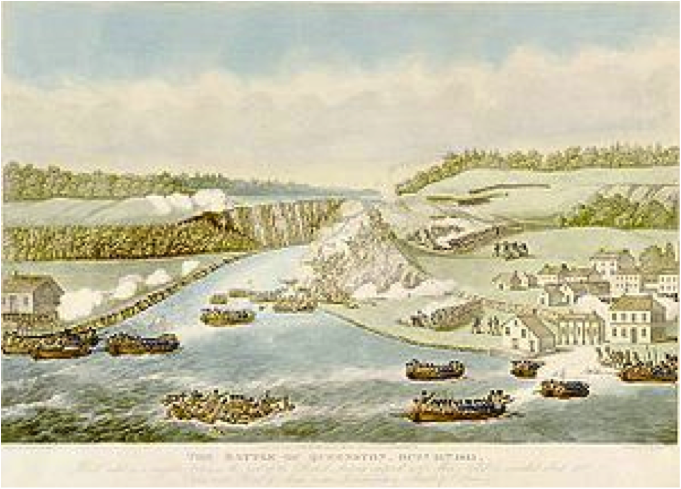

In this two-century, multi-generation migration, the Love family was part of the larger migration patterns in the U.S. Many descendants of families who came to New England in colonial times moved westward, following the retreating frontier. The end of the Revolutionary War opened up territory in Western New York, and the War of 1812 expanded the American frontier to the Great Lakes states. The Erie Canal, built in 1825, made travel accessible for large numbers of families with their livestock and household supplies, as they moved from the depleted farms of New England and eastern New York to virgin lands around the Great Lakes.

The California Gold Rush and opening of lands in the Willamette Valley in Oregon encouraged the children and grandchildren of those earlier pioneers to continue the generational movement westward in wagon trains on the Oregon Trail. After the Civil War, railroads built across the west provided a fast and safe mode of transport from the east clear to the Pacific shore, and shortly after the railroads were built, the age of the automobile made travel even easier.

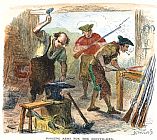

The work of homesteading required large families, but when the children were grown, they needed to establish farms of their own. Source: North-wind picture-archives. Hand-colored woodcut of a 19th-century illustration.

The spirit of adventure and the promise of economic security through homesteading large tracts of wilderness were undoubtedly motivations for these migrations. By the early nineteenth century, some lands in New England had been cultivated for almost two hundred years and had lost productivity. Families were large, and the farms were often divided among the children as they came of age, so the farms became smaller over the generations. While some siblings would stay on the home farm, others would move to new lands and opportunities further west. In this way adult children became geographically separated from their parents and from one another. The permanent separation of families and social isolation of individuals are other recurring themes in our family saga.

Sources: Two family histories provide much of the material for the narratives here. William Deloss Love, Jr. (1851-1918) wrote Love Family History (1918) based on notes of his father and his own research. He was the great-grandson of Robert and Susanna Love; his grandfather was William Love, a brother of our direct ancestor, Levi Love. William Deloss Love, Jr.’s work is the main source of information for Adam and Mary Love, Sgt. Robert and Sarah Love, and Robert and Susanna Love. Dorothy Love McKillop (1943- ), and Mary Anne Blaisdell Love (1948-) descendants of Levi and Eunice Love, wrote another Love Family History in 1991, bringing the narrative forward. Their book is the main source of information for Levi and Eunice Love. These and other sources are listed in the Footnote section at the end of this essay.

FIRST GENERATION

Adam (1697-1765) and Mary (1702-1776) Love: From Northern Ireland to Rhode Island

Adam and Mary Love and their young daughter emigrated from Northern Ireland to Rhode Island in about 1730. According to a family story, Mary gave birth to their second child, our ancestor Robert, on ship. The Loves traveled with Adam’s brother Gabriel, part of a larger movement of farmers leaving the economic hardship in Antrim County, Northern Ireland, for the promise of economic opportunity in the new world.

Jury duty in colonial Rhode Island often meant convening a temporary court at the site of the crime, so the jurors could examine the evidence. See the outdoor court in center of picture.

Adam and Mary homesteaded in a wilderness area about ten miles west of the town of Warwick, Rhode Island. A consortium of settlers had purchased this land from the Narragansett Tribe of Indians in 1642. Over the years, the Loves helped to create the town of Coventry. Public records show that they bought and sold various farms and paid taxes that were above the average for the area. Adam was elected as a jury man several times, and also served as town constable. In colonial America, in resistance to British oppression, juries fulfilled an important political function of protecting individual liberties.

However, the records also show that Adam was sued or otherwise involved in legal problems. Adam was forced to declare bankruptcy at one point. According to family historian W. D. Love, the bankruptcy resulted from his effort to secure farms for his adult children: “The gifts he had made to his sons, were, however, more generous than he could afford” (p.26). Adam was in his early 60s at the time; he spent his remaining few years living with his wife on the property of his son, William. He died at age 68 in 1765. Adam and Mary Love had two daughters and three sons; all but the oldest daughter were still living at the time of Adam’s death. Mary lived for another 11 years, and is buried by her husband in Riverside Cemetery (also known as Oneco Cemetery), Sterling, Connecticut.

However, the records also show that Adam was sued or otherwise involved in legal problems. Adam was forced to declare bankruptcy at one point. According to family historian W. D. Love, the bankruptcy resulted from his effort to secure farms for his adult children: “The gifts he had made to his sons, were, however, more generous than he could afford” (p.26). Adam was in his early 60s at the time; he spent his remaining few years living with his wife on the property of his son, William. He died at age 68 in 1765. Adam and Mary Love had two daughters and three sons; all but the oldest daughter were still living at the time of Adam’s death. Mary lived for another 11 years, and is buried by her husband in Riverside Cemetery (also known as Oneco Cemetery), Sterling, Connecticut.

For more on Adam and Mary Love, including a discussion of their legal issues, click here.

SECOND GENERATION

Sgt. Robert (c. 1730-1809) and Sarah Blanchard (1743-1771) Love: From aboard ship in the Atlantic Ocean to Coventry, Rhode Island

Robert, the oldest son of Adam and Mary Love, was born about 1730, probably on the ship that brought his parents from Northern Ireland to America. He grew up helping to clear the family homestead farm in the wilderness in Coventry, RI. In 1753, when he came of age, his father gave him a portion of the homestead farm, about 80 acres. As a young adult, he farmed this land and also probably worked as a blacksmith. Over the next fifteen years, he suffered such serious financial hardships that his farm was in danger of being repossessed for back taxes. Fortunately, his mother, Mary Love, satisfied the claim by relinquishing one of her silver spoons to the sheriff.

During these years, Robert married three times. He had a daughter by each of the first two wives; both women died in childbirth, and their daughters were raised in the homes of grandparents.

Robert married for a third time in 1762, to our ancestor, Sarah Blanchard (born 1743 in Rhode Island), whose family’s farm adjoined that of Robert Love. She died in 1771, at age 28, leaving three children, including our ancestor Robert Love, Jr. She was “a woman of excellent family and character, and her death was a serious loss to the family circle” (W.D. Love, p. 71). Her parents were Anne Whaley and Moses Blanchard, whose families were early settlers in Rhode Island. Sarah Blanchard’s great grandfather was Theophilus Whaley, a mysterious historical figure; I have written about him here.

Soldiers at the siege of Yorktown, 1781, by Jean Baptiste Antoine DeVerger. The Black soldier on the left wears the uniform of a Rhode Island regiment.

In 1773 , his oldest daughter, Olive, by his first wife, moved from the home of her grandmother, Mary Love, to that of her father. She was 16 years old and assumed the duties of managing the household and her three younger half-siblings, probably with the help of her grandmother, Mary Love. Sgt. Robert Love left her in charge of the household and enlisted in a Rhode Island regiment in 1777, to serve in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. He remained in service for three years and three months, as verified by the database of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR).

Over the years before and after the War, Sgt. Robert Love sold off the property he had inherited, much of it to his brother, William. During his later years he lived on property that his children by Sarah Blanchard had inherited from their maternal grandfather, Moses Blanchard. According to W.D. Love, he built a blacksmith shop on this land. He married for a fourth time in 1791; there were no children from this marriage. Robert Love died in Coventry in 1809. In assessing his character, W. D. Love wrote:

“Sergeant Robert Love seems . . . to have been a man of unusual energy. He was industrious, resourceful and patriotic, tenacious, doubtless, of his rights and very likely careless in the management of his affairs – a man whose life passed amid a variety of experiences and was repeatedly broken up by affliction, but a man who had that courage and perseverance which have characterized so many of his descendants.” (W.D. Love, p. 70)

Robert had three daughters and two sons; all were living at the time of his death except his oldest son, Alexander, who died a soldier in the Revolutionary War. According to W. D. Love, he is probably buried in the Riverside Cemetery (also known as Oneco Cemetery) near his parents and other kindred, but his gravestone has not been found.

THIRD GENERATION

Robert (1767-1836) and Susanna Austin (1766-1842) Love: From Coventry, RI to Bridgewater, NY

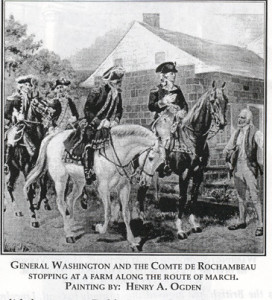

This picture shows General Washington meeting the French General Rochambeau in Rhode Island and traveling to Yorktown for the definitive battle of the Revolution. This could have been the cavalcade that young Robert Love observed from the family farm.

Robert was born in 1767 in Coventry, RI, and grew up on his father’s farm. His childhood was disrupted by the death of his mother, Sarah Blanchard, when he was four, leaving him and his two older siblings in the care of his father and later of his older half-sister, Olive Love. When Robert was ten, his father and older brother, Alexander, left home to fight in the Revolutionary War for three years, and his brother never returned, having died in service. The War was a pervasive presence close to home; a family story states that Robert watched General Washington and a contingent of soldiers pass by the family farm during military maneuvers. After the War, when Robert was sixteen, the family was permanently broken up when Olive got married and left home, and Robert’s father, Sgt. Robert Love, sold the family property to his brother, William.

Young Robert, now out on his own, worked as a laborer for several years, and then made his way about thirty miles west to Preston, Connecticut, where he continued to work for others. There is no record that he owned land in Preston, but he did have an interest in land back in Coventry, RI. This was the farm that his grandfather, Moses Blanchard, had left to his children. Sarah, Robert’s deceased mother, had inherited a one/sixth share of her father’s estate, and this share was divided among Sarah’s two surviving children. This was too small a parcel to support Robert and his family, and in 1785 he sold it to his father, and left Rhode Island for good.

Susanna Austin Love and the Congregational Church in Preston, Connecticut

John Gano, Baptist minister, baptizing George Washington at Valley Forge. The authenticity of this alleged event is much disputed. It is certain that George Washington was baptized as an infant in the Episcopal Church..

In 1788, at age 21, Robert married Susanna Austin in the Congregational Church in Preston. The pastor was the Rev. Levi Hart, a prominent and influential preacher in Connecticut.

The family’s involvement with this church began a generation earlier, in 1762, when Susanna’s parents, Benjamin and Sarah Burdick Austin, came to Preston from Rhode Island. Sarah was descended from founders and leaders of the Seventh Day Baptist Church in Rhode Island, dating back to the 1600s (click here). A key tenet of the Baptist Church was adult, not infant baptism. Therefore, it was very significant when, in 1768, Sarah broke with this tradition, formally joined with Rev. Hart’s Congregational Church , and had all six of her children baptized.

One of those children was our ancestor, Susanna. Susanna, in her turn, formally joined the Church after her marriage to Robert and later had her children baptized there, including our ancestor Levi. In those days, joining the Congregational Church was a major commitment, and not undertaken lightly. Robert did not join, but, like many others, was part of the larger church family.

Design of the medallion created as part of the anti-slavery campaign by Josiah Wedgwood, English potter, 1780.

The Loves’ involvement in Rev. Hart’s church put them in the center of one of America’s great social reforms, the Abolitionist Movement. Historian Peter Hinks called Rev. Levi Hart one of the “most important critics of slavery to emerge in Connecticut during the years of the American Revolution.” In 1775 he preached a sermon that pointed out the hypocrisy of fighting for freedom from Britain while maintaining slavery:

“Could it be thought then that such a palpable violation of the law of nature, and of the fundamental principles of society, would be practiced by individuals and connived at, and tolerated by the public in British America! . . . .

What have the unhappy Africans committed against the inhabitants of the British colonies and islands in the West Indies, to authorize us to seize them, or bribe them to seize one another, and transport them a thousand leagues into a strange land, and enslave them for life?” ( Liberty Described and Recommended, 1775.)

After the war, he helped form the Connecticut Society for the Promotion of Freedom and the Relief of Persons Unlawfully Holden in Bondage, organized in 1790. In addition to lobbying the legislature to abolish slavery in Connecticut, the Society assisted African-Americans, both slave and free, from the terrible threat of kidnapping and being transported to slave-holding states.

After the war, he helped form the Connecticut Society for the Promotion of Freedom and the Relief of Persons Unlawfully Holden in Bondage, organized in 1790. In addition to lobbying the legislature to abolish slavery in Connecticut, the Society assisted African-Americans, both slave and free, from the terrible threat of kidnapping and being transported to slave-holding states.

Robert and Susanna Love were actively involved in the Church during the years of Rev. Hart’s public leadership to abolish slavery and no doubt heard many sermons on subject. Their devotion to Hart is shown by the naming of their first son after him, our ancestor, Levi Love. We don’t know their personal views on slavery, but the record clearly shows that as participants in this church, they were embedded in the social and moral environment of the New England abolitionists.

Migration to Bridgewater, New York

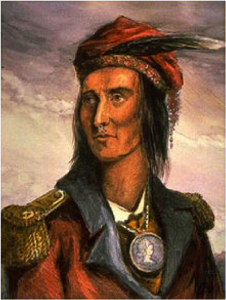

In the spring of 1794, when Robert was 26 years old, he and Susanna and their three young children left Preston to follow a migration trail to Oneida County, New York, a distance of about 220 miles. This land became available for settlement after the Revolutionary War, as a result of U.S. conquest and treaties with the Iroquois Confederacy of Native American tribes, who moved to reservations or to areas further west.

Early stage of settlement in the wilderness, showing how life might have looked in Bridgewater in the 1790s.

This new “promised land,” included potentially fertile farm land in the wilderness along the Umadilla River. At the time that the Love family arrived in Bridgewater, it was no more than a clearing in the forest consisting of about two dozen families. The migration from New England to western New York was largely a phenomenon of young families wanting to build an economic future for their children. At Bridgewater in 1800, 400 of the 1,000 residents were under the age of 10 and most of the rest were their parents. Only 77 people were over the age of 45.

Western New York farm several years after first settlement. Source: Pioneer History of the Holland Purchase of Western New York (1850)

Over the next few years, the Loves incrementally bought land, which comprised a total of 135 acres in 1811. But then the fortunes of the Love family declined quickly. Love invested in locally raised cattle with the expectation that they would be driven to Albany to be sold for export. This was potentially quite profitable, but the looming War of 1812 intervened. An embargo was placed on exporting beef, causing the price to fall steeply. Love lost heavily, and his homestead was sold for debt in August, 1811.

Western New York farm in a later stage of settlement. Source: Pioneer History of the Holland Purchase of Western New York (1850)

According to W. D. Love, Robert “grieved for years over his ill fortune and never fully recovered from its discouragement”. However, he enlisted briefly in the military to defend Sackett’s Harbor during the War of 1812. After the war, he was slowly able to acquire farmland again, partly by buying properties belonging to his now adult children. He died on his farm in Bridgewater in 1836, at the age of 69.

Robert and Susan Love tombstones, with medallion for service in War of 1812. Fairview Cemetery, Bridgewater, NY. Photo courtesy of Judy Love.

His wife, Susanna Austin Love, died in 1842. According to W. D. Love, she was a strong influence in the family. She was consistently mentioned in letters with “respect and affection” and was remembered for her many good deeds. She was particularly interested in the religious education of her children and grandchildren. Susanna was buried beside her husband in Fairview Cemetery in Bridgewater.

The Loves had eleven children, only one of whom (Alice Love Steele) remained in Bridgewater. The rest of the children scattered throughout New York, Michigan, Wisconsin and elsewhere in the Midwest, continuing the Love’s multi generational migration westward.

FOURTH GENERATION

Levi (1790-1875) and Eunice Waldo (1791-1867) Love: From Preston, Connecticut to Waukesha, Wisconsin

Levi Love was born in Preston, Connecticut in 1790, the second of eleven children. His parents, Robert and Susanna, named him after Rev. Levi Hart, the Abolitionist pastor of the Congregational Church in Preston, which they attended. Levi immigrated to Bridgewater, New York with his family when he was three years old. Young Levi grew up helping on the family farm, and attending the local village school and Congregational Church.

Eunice (Dimmock) Waldo Love

One of his childhood companions was Eunice Waldo, whom he married in Bridgewater in 1808 when they were 17 and 18 years old, respectively. Eunice’s ancestry traces back to the earliest pilgrims. Among her maternal predecessors were the famous Governor of the Plymouth Colony, William Bradford and his wife, Alice Southworth Bradford. Two other ancestors were involved in the Revolutionary War. Her grandfather, Jesse Waldo, fought with a Connecticut regiment of the Continental Army from 1774 to 1777. Her mother’s mother, Phebe Turner, as a young widow with four daughters to raise on her own, nonetheless lent the State of Connecticut over 117 pounds, a sum that represented more than half the value of her estate, for the war effort. The debt was still outstanding at the time of her death (Daughters of the American Revolution database). Through her Waldo line, we are also distantly related to Presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams, and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Eunice had immigrated to Bridgewater as an infant with her parents, Ephraim and Eunice (Dimmock) Waldo. Family historian Waldo Lincoln recorded an account of the journey the Waldos, along with two other families, made from their home in Mansfield, Connecticut into the wilderness of western New York in about 1791:

“They came by way of Albany, up the valley of the Mohawk to Whitesboro and from thence by the way of Paris Hill to Bridgewater. From Paris Hill they were obliged to make their road as they progressed, following a line of marked trees. Their team consisted of two yoke of oxen and a horse and the vehicle of an ox sled. They arrived on the 4th of March. The snow at this time was about one and one half feet deep but soon increased to the depth of four feet. They had two cows which, with the oxen and horse, subsisted, until the snow left, upon browse alone. Upon their arrival they erected a shanty of the most primitive style. Four crotched sticks set in the ground, with a roof of split basswood overlaid with hemlock boughs, with siding composed of coverlets and blankets, formed the first dwelling house ever erected in the town of Bridgewater. The three families continued in this miserable apology for a house until midsummer, when two of them, having more comfortable dwellings provided, removed to them while the other remained for a year.” (Lincoln, pp. 326-328)

Exploring the Great Lakes Region

Levi and Eunice Love settled to a life of farming in Bridgewater. The War of 1812 disrupted the family; Levi’s father, Robert, went bankrupt and both Robert and Levi joined the army for the defense of Sackett’s Harbor on Lake Erie. Eunice’s father, Ephraim, was killed in the War.

When they were nearly forty years old, Levi and Eunice followed the Love family pattern of each generation moving west; they moved three times in the next fourteen years, starting in 1829. The Loves were part of a tide of New Englanders who rapidly populated the territories around the Great Lakes, which started to open for settlement after the War of 1812.

When they were nearly forty years old, Levi and Eunice followed the Love family pattern of each generation moving west; they moved three times in the next fourteen years, starting in 1829. The Loves were part of a tide of New Englanders who rapidly populated the territories around the Great Lakes, which started to open for settlement after the War of 1812.

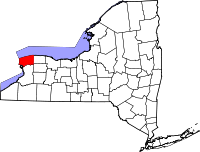

Their first move was in 1829, soon after their twelfth child was born. In that year the family left Bridgewater and moved about 200 miles west, to Hartland, a farm community in Niagara County, New York. Eunice’s parents had moved there many years earlier, so the Loves were certainly familiar with the region.

A great spur to their migration was the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825, which went from Albany, NY, on the Hudson River, west to Buffalo, NY, on the shores of Lake Erie. The Loves and their twelve children almost certainly traveled by barge along the canal to their new homestead in Hartland. Although barge travel was crowded, dirty, and uncomfortable, it was much faster and easier than the journeys the Loves’s parents had made by foot and ox cart a generation earlier from Connecticut to the wilderness of Bridgewater, New York.

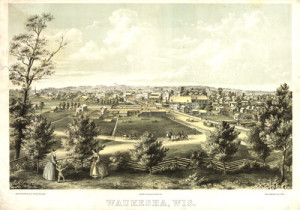

After seven years in Hartland and the birth of two more children, for a total of fourteen, the Loves were on the move again. In 1836, Levi traveled with his brother, Robert, to Waukesha (then called Prairieville), Wisconsin, on the western shore of Lake Michigan. Earlier in 1836 the Federal Government, having removed the Native American residents who had been living there, created Wisconsin Territory, surveyed the land, and opened it for settlement. No doubt the Loves, like many other New Englanders, wanted to be among the first to claim homesteads in this potentially very fertile agricultural region.

Robert Love and his family stayed and homesteaded in Wisconsin, but Levi returned to Hartland. We don’t know what his intentions were for the trip to Wisconsin – whether he was simply going to reconnoiter, or whether he had hoped to homestead there like his brother, and for some reason did not.

Whatever the reasons for his trip to Wisconsin, it is clear that the Levi Love family was planning to leave Hartland permanently, because they did so soon after Levi returned. Instead of Wisconsin, they moved moved 170 miles west across the Niagara River into southern Ontario, Canada, not far from the northern shore of Lake Erie. We would like to know more about the reasons for the decision to move there, but unfortunately I have found no information on this.

The move to Canada also proved to be temporary, and in 1843 the family moved for the third time, to their fourth and final location. After a brief return to Hartland, the Loves joined Robert, Levi’s brother, in Waukesha, Wisconsin. By this time several of the older children were grown and out on their own, and only eight of their fourteen children, ranging in age from 8 to 32, accompanied their parents to Wisconsin.

To the eight year old Julius Caesar Love, Levi and Eunice’s youngest son, the journey was an adventure. Years later he recounted his experiences:

“We started with two sleighs and two teams of horses, with wagons set on the sleighs and the wheels fastened onto the loads. I think I rode about half of the distance on the wheels and that part of the reach that extended beyond the wagon.

Ox cart in snow, Vincent Van Gogh, 1884 The ox cart was indispensable in pre-industrial societies throughout the world.

The wagons were loaded with household goods and provisions . . . . . We stopped three times to cook up a quantity of food and every night we stayed all night at a tavern (NO liquor tavern.) When night came on we would run out in the road to see if we were coming near to a tavern. We were cold and hungry and a sign of a tavern was welcome. They always gave us a room to prepare our own food.

When we were going through Northern Indiana the snow went off and we sold our sleighs and started the remainder of our journey on wagons. But, when we reached Southport [now called Kenosha] we found deep snow. Father hunted around to find sleighs and found a man who wanted to send a sleigh to Milwaukee, and trusted Father to deliver it. Father also bought one sleigh. We arrived in Milwaukee on March 23, 1843, at 8 o’clock, pm. They were having the “River and Harbor Celebration.” Father went to look for his brother, Robert Love, and found him upon the platform, one of the speakers. (Dorothy McKillop, p. 67-68)

Waukesha, Wisconsin, 1857, fourteen years after the Love family homesteaded on a farm near the town.

Levi and Eunice bought a 243 acre homestead claim from Levi’s brother, Robert. The land had only a log cabin, 16 by 20 feet. Levi, Eunice, and their eight children all lived there for the first two months, along with another brother of Levi’s, Henry Love, who arrived from Milwaukee with his family of four. Then the family built a large addition, where the family settled permanently. According to Julius Caesar Love, “For this new home Father turned in one team and wagon in part-payment, and we traded one horse for a yoke of oxen and a cow and bought another yoke of oxen and paid off that by plowing and I was usually one of the drivers and not yet nine years old. (Dorothy McKillop, p. 68)

Eunice died there in 1867. Levi, now age 77, remarried almost immediately. His second wife, Elizabeth, also predeceased him. Levi died at age 85, in 1875, by drowning when he slipped and fell into a spring where he was dipping his pitcher for water. According to his obituary, “his temperate life had enabled him to escape many of the infirmities of so great an age.” He is buried by his first wife, Eunice, in Prairieville Cemetery. His obituary refers to him as “Deacon Love;” the title implies that he had a leadership role in a church, quite likely the Congregational Church founded by his brother, Robert Love.

Part 2 of the Love Family Saga is forthcoming. It will follow the Love family line from Levi and Eunice’s son, Lorenzo Love, to George Love, and then to my grandfather, Olin Love.

References

Adam and Mary Love: Jones, Maldwyn A. (1980) Scotch-Irish. In Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, ed. Stephan Thernstrom, Boston, MA: Harvard University Press, p. 896; Love, William DeLoss, Jr. (no date, but prior to 1918) Love Family History. Hartford, CT: Unpublished manuscript; A Brief History of Warwick, Rhode Island, available online at http://warwickhistory.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=88:a-brief-history-of-warwick-rhode-island&catid=40:introduction-to-warwick-history&Itemid=130, accessed 2016; Dialogue on the American Jury: We the People in Action, available on line at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/migrated/jury/moreinfo/dialoguepart1.authcheckdam.pdf, accessed 2016.

Sgt. Robert and Sarah Love: Love, William DeLoss, Jr. (no date, but prior to 1918) Love Family History. Hartford, CT: Unpublished manuscript, p. 67; DAR (Daughters of the American Revolution), Robert Love Ancestor No. A071843.

Robert and Susanna Love: Love, William DeLoss, jr. (no date, but prior to 1918) Love Family History. Hartford, CT: Unpublished Manuscript; U. S. Federal Census, 1790, for New London, Connecticut, Robert Love.; Connecticut Town Marriage Records, pre-1870 (Barbour Collection), Ancestry.com, database on line, Provo, UT, accessed 2006; Connecticut Church Record Abstracts, 1630-1920, Ancestry.com, data base on line, Provo, UT, accessed 2013; The United Methodist Church, What’s the difference between infant baptism and believer’s baptism? Available on line at www.UMC.org, accessed 2016; Hinks, Peter P. Early Anti-Slavery Advocates in 18th Century Connecticut. Available online, www.connecticuthistory.org, accessed 2016;Editors of the Encyclopedia Britannica, Iroquois Confederacy, available on line at www.britannica.com, accessed 2016; U.S. Federal Census, 1800, 1810, 1820, 1830 for Bridgewater, Oneida County, New York, Robert Love.

Levi and Eunice Love: Love, William DeLoss, jr. (no date, but prior to 1918) Love Family History. Hartford, CT: Unpublished Manuscript; Lincoln, Waldo (1902), Genealogy of the Waldo Family, Charles Hamilton Press: Worcester, Mass.; Connecticut Church Record Abstracts, 1630-1920, Ancestry.com, data base on line, Provo, UT, accessed 2013; Daughters of the American Revolution, Jesse Waldo, Ancestor No. A120688, and Phebe Turner, Ancestor No. A036936; Jones, Pomroy, (1851) Annals and Recollections of Oneida County, Rome, NY: Published by the author, pp. 125-127, as quoted in Lincoln, Waldo (1902); Turner, O. (1850), Pioneer History of the Holland Purchase of Western New York, Buffalo: Jewett, Thomas & Co.; Love, Dorothy, and Anne Blaisdell Love (1991), Love Family History, Seattle: Unpublished manuscript; U.S. Census, 1830, Hartand, Niagara County, NY; U.S. Census, 1850, 1860, Pewaukee, Waukesha County, WI.; “Death of Deacon Love”, Waukesha Freeman, Nov. 18, 1875, as quoted in Love, Dorothy, p. 70.