Ministers’ Monument, in Hopkinton, Rhode Island, commemorates the founders of the Baptist Church in America. Two of the pastors and one pastor’s wife named on the monument, John Maxson, Mary Maxson, and John Maxson, Jr., are our direct ancestors. Other pastors listed, of the Burdick and Clarke families, were relatives of our ancestors. These first immigrants to America were pioneer settlers in Rhode Island and helped in its founding.

Into the Wilderness with Roger Williams

After being evicted from the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1636 for unorthodox religious beliefs, the Puritan preacher Roger Williams walked into the wilderness to an area he named Providence Plantation, now part of Rhode Island. The first principles of the new Colony were separation of religious and civil authority and absolute freedom of religion, which Williams called “soul-liberty.” Thus, from the beginning, Rhode Island was intended to be very different from its sister colonies, Massachusetts and Connecticut, where rigid religious oligarchies held sway. Because of its religious toleration, Rhode Island became a haven for Quakers, Jews, Huguenots, and other dissenters. Several of our ancestors followed Roger Williams to Rhode Island, and helped him found there the Baptist Church in America.

Tase Cooper and Samuel Hubbard

Rhode Island pioneers were hardy people who were prepared to organize their lives around their religious convictions. Among them were our double-ancestors (ancestors through two lines) Tase Cooper and Samuel Hubbard, an early “power couple” in the Colony and the Baptist Church.

Tase Cooper came to America in the 1630s, apparently as a single woman. In the hard winter of 1635 she was one of a hundred people who walked from the Massachusetts Bay Colony to become the first settlers in Connecticut. There she married Samuel Hubbard, another member of the group. A Baptist herself, she persuaded her husband to also become a Baptist, and they suffered persecution for it in Connecticut and Massachusetts. According to Samuel Hubbard’s diary:

“She was mostly struck at and answered two times publicly, where I was also said to be as bad as she and sore threatened with imprisonment at Hartford jail.” (1)

On this account the Hubbards moved to Newport, Rhode Island in 1648, and lived there the rest of their lives. They were pillars of the Sabbatarian Baptist Church, an offshoot of the Baptist Church whose adherents celebrated the Sabbath on Saturday. William Clarke Whitford, a historian of the Sabbatarian Baptist Church, wrote that Tase Cooper Hubbard was:

“A woman of superior discernment and moral courage, the first convert to the Sabbath in America, truly a sainted mother in our Israel, and the ancestress of all the Burdicks, the Langworthys, nearly all the Clarkes, and their posterity, who have ever been received into our churches.” (2)

Her husband, Samuel Hubbard, came from a long line of Protestant dissenters in England. His grandfather had been burned at the stake during the reign of Queen Mary (Bloody Mary) for refusing to recant his Protestantism. After he and Tase moved to Rhode Island, he became one of the most active and influential members of the Baptist Church in Newport. He was also a prominent figure in the Colony, and was appointed deputy Solicitor General. According to family historian William DeLoss Love,

“Samuel Hubbard was made a freeman of the Colony in 1655. He had a large interest in its welfare. His friendship for Roger Williams, formed at Salem, continued through his life. Other distinguished men of Rhode Island held him in esteem. Though somewhat ready to engage in religious controversy he was a man of amiable disposition, devout spirit, unblemished character, and kindly disposed to all mankind.” (3)

“Rogue Islanders”

The theocratic leadership of Connecticut and Massachusetts was deeply suspicious of the freedom of religious conscience in Rhode Island. They referred to Rhode Island inhabitants as “Rogue Islanders,” “fanatics,” turbulent inhabitants,” “living in imbecile condition,” and “guilty of outrageous practices.” They determined to attack the Colony by claiming a large portion of land that Rhode Island also claimed for itself, notably most of the area west of Narragansett Bay, called Westerly (see map). The stakes were high in this land dispute, because if Rhode Island lost Westerly, the colony would be reduced to two towns along the Bay and would probably lose its standing as an independent political entity in New England. (4) In order to strengthen the claim of Rhode Island to this disputed land, in 1661, our ancestors, Ruth, daughter of Tase and Samuel Hubbard, her husband Robert Burdick, Joseph Clarke, Jr. (later to marry Ruth’s sister, Bethiah) along with a few others, moved into this largely uninhabited territory.

Robert Burdick, Joseph Clarke, and a third pioneer, Tobias Saunders, were promptly arrested by an agent of the Massachusetts Bay Colony for illegally settling in the area, and brought to trial in Boston. The “Rogue Islanders” were defiant, and disputed the jurisdiction of the Massachusetts Court to hear the matter. They refused to pay the fine the court imposed, and were therefore imprisoned for two years in Boston. Their imprisonment ended when Rhode Island seized two Massachusetts agents, and there was a prisoner exchange. (5) Eventually, the dispute was resolved in England, which divided the land between Connecticut and Rhode Island. Meanwhile, Massachusetts put constant pressure on the Rhode Island settlers, threatening them with imprisonment and fines if they refused to leave. The settlers chose to remain, however. Demeaned as ‘intractable backwoodsmen,’ the firmness of the people of Westerly, according to historian William Clarke Whitford, preserved Rhode Island as an independent colony, and thereby also was instrumental in keeping alive the principles of religious freedom and the separation of church and state in New England. (6)

Exhausting Toils in Westerly

Samuel and Tase Hubbard’s daughter, Ruth, was the first child of European immigrants born in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1640. She was raised in Newport, in the Baptist Church her parents founded there. At the age of fifteen she married Robert Burdick, and when she was 21 she moved with him to the Westerly area of Rhode Island. She may have stayed in Westerly during his two year imprisonment in Massachusetts, and they certainly made their home there after his release.

(7) William Clarke Whitford presented a picture of life in the Westerly Baptist community. It could be a description of the Burdick’s life, somewhat idealized:

“As you enter the only room in one of these rude dwellings, you see the few families . . . gathered there for an evening visit. The group form a half-circle in front of the wide fireplace, in which the blazing logs or faggots light up the serious faces of the older members, giving them a glow of cheerfulness, and revealing to you also the rough, home-made furniture. They are earnestly talking about . . . their trials and adventures while on the way to this purchase . . . their exhausting toils in subduing the ground and in providing sufficient food and home-spun clothing for themselves . . . They calmly and understandingly discuss the immutable claims of God’s weekly Sabbath upon their consciences, an obligation recently first apprehended by them. The conversation is interrupted as nutritious nuts, collected in the woods about them, cracked and ready for eating, are passed to each one in the company.” (8)

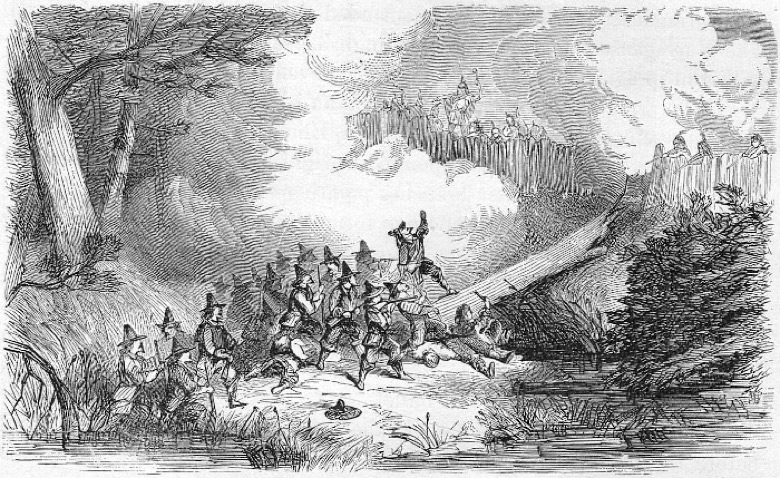

The Great Swamp Fight

Pioneer life was interrupted by serious Indian trouble. Roger Williams had maintained good relations with the Indians, but the encroachment of white settlement over the next forty years, coupled with Indian-settler clashes in the other colonies, created a volatile situation. The threat of an Indian uprising was always in the background among the Westerly pioneers. In 1666, Ruth Hubbard Burdick wrote to her parents in Newport, Samuel and Tase Hubbard:

“My longing desire is to hear from you, how your hearts are borne up above these troubles which are come upon us and are coming as we fear; for we have the rumors of war, and that almost every day. Even now we have heard from your Island by some Indians, who declared unto us that the French have done some mischief upon the coast, and we have heard that 1200 Frenchmen have joined with the Mohawks to clear the land both of English and of Indians. But I trust in the Lord, if such a thing be intended, that he will not suffer such a thing to be.” (9)

Great Swamp fFght

In spite of her hopes, New England erupted in a terrible conflict known as King Phillip’s war. Soldiers from neighboring colonies invaded Kingston, R.I., and slaughtered local Indians, who until then had been neutral in the war. This event, known as The Great Swamp Fight of 1675, brought Rhode Island into the conflict. In his diary, Samuel Hubbard reported how he evacuated his daughters Ruth and Bethiah from Westerly.

“In the midst of these troubles of the war Lieut. Joseph Torrey, Elder of Mr. Clarke’s Church, having one daughter living at Squamicut and his wife being there, he said unto me `Come, let us send a boat to Squamicut, my all is there, and part of yours.’ We sent a boat, and his wife, his daughter and son in law and all their children and my two daughters, and their children (one had eight, the other three, with an apprentice boy) all came. …My son Clarke came afterwards before winter, and my other daughter’s husband in the spring, and they have all been at my house to this day.” (10)

In 1676 the War ended, and Rhode Island, except for the burning of Providence, was generally spared massive destruction.

100 Years Later

About a hundred years after her ancestors came to Rhode Island to establish the Sabbatarian Church, our ancestor, Susanna Burdick, great great-granddaughter of Tase and Samuel Hubbard, and great-granddaughter of Ruth Hubbard and Robert Burdick, was born, in 1736. She grew up in the church in Hopkinton, R.I. where her relatives had been leaders for generations. In 1759 she married Benjamin Austin, who was not a Baptist, and may have been of Quaker background. Compared to the staid Burdicks, the Austins were a more contentious family. Benjamin’s grandmother had made a public complaint that she could not live peaceably with her son-in-law, Benjamin’s father. After his father died, Benjamin probably left home to learn a trade, and his mother took two of her remaining sons to court, complaining that they refused to work for her or anyone else to earn their keep. (11)

The records on the family do not indicate that Susanna’s marriage caused a breach with her family. Her father sold land to the young couple near his own farm, which was a standard way for parents to help their children get a start in life. However, two years after their marriage, Susanna and Benjamin Austin left the family home in Hopkinton, and moved to Preston, Connecticut, fifteen miles way. There Benjamin probably followed the trade that he had learned in his apprenticeship. (11)

Levi Hart

In Preston, the couple fell under the influence of a prominent local Congregational minister, the Rev. Levi Hart, (pictured) and they both became regular attendees of his church. Levi Hart is best known today for a 23 page letter he wrote advocating the abolition of slavery, which became a foundational document of the abolitionist movement. Susanna Burdick Austin became a member of the Congregational Church in 1768. She also brought her six children to be baptized.

One of the children, Susanna Austin, celebrated her second birthday on the day of the family baptism. She grew up to marry Robert Love, another member of Levi Hart’s congregation. This couple were so influenced by this preacher that they named their oldest son after him, our ancestor Levi Love. (11)

Susanna Burdick Austin’s decision to have her children baptized was remarkable. A key tenet of the Baptist faith of her forbearers, and a reason for their break with other Puritans, was that baptism should be reserved for adults, who could make a reasoned choice, and not be imposed on children too young to think for themselves. Thus, in having her children baptized, some of whom were infants, she emphatically ended the family connection with the Baptist Church.

The story of these early Baptist pioneers in Rhode Island is an important part of our Love family history. Their lives reflect their deep religious convictions, which had been the reason that they had come to America, and guided their lives while they were here. They hoped to create a society following the mandates they saw in the Bible. Their religious faith sustained them during the difficult trials of settling the wilderness, the unrelenting labor, isolation, early deaths, and the constant threat of Indian attacks. Their Baptist beliefs led them to the principles of the separation of church and state and religious toleration, which they fought to preserve in Rhode Island. They helped to make Rhode Island a standard bearer for liberty.

A hundred years later, by the middle of the eighteenth century, the wilderness had been largely won in New England. Many people found the religious controversies of the previous century “deeply boring.” New immigrants came to America for economic opportunity. Benjamin and Susan Burdick Austin’s descendants, our Love ancestors, turned their energies to fighting in the Revolutionary War and to economic betterment. They were interested in religion that would help make life better and resolve social problems, such as slavery, and the old religious controversies no longer seemed so important.

The Congregational Church in Preston, Connecticut

How you are related to our Baptist ancestors in early Rhode Island

On your personal ancestor fan, find Levi Love on the outermost ring. Then, click here to open the Levi Love Ancestor Fan, and find his mother, Susanna Austin. All of the Rhode Island ancestors mentioned in the post extend back from her, in the yellow section of the Fan.

References

1. William DeLoss Love, Love Family History. Unpublished manuscript, Hartford CT. p. 169.

2. William Clarke Whitford, Address, Dedication of Ministers’ Monument, Aug. 28, 1899. First Hopkinton Cemetery Association, Hopkinton, R.I. Printed by the American Sabbath Tract Society, Plainfield, N.J., 1899 p. 19.

3. Love, p. 170.

4. Whitford, pp. 15-16.

5. Nellie Willard Johnson, The Descendants of Robert Burdick of Rhode Island. Syracuse, N.Y. The Syracuse Typesetting Co., Inc. 1937, pp. 1-6.

6. Whitford, pp. 16-17.

7. Johnson, pp. 1-6.

8. Whitford, p. 12.

9. Johnson, p. 1-6.

10. Online: http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.com/~hubbard/hubbard_photos/hubbard_thomas_tree.htm

11. Love, pp. 75-76, 95. Dorothy Love McKillop, Love Family History, Unpublished manuscript, Seattle, WA, 1992, p. 01.